News Sharing On- and Offline

A new theoretical model for understanding news sharing as a common practice, both on- and offline.

News outlets and journalism researchers frequently focus on how news is shared on social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and TikTok—unsurprisingly, given that half of U.S. adults report getting news from such sources "sometimes" or "often" (Pew Research, 2022). It's easy to think of social media platforms as radically different from more old-school communication. However, in a new paper published in Journalism Practice, Knology researcher Jena Barchas-Lichtenstein presents a theoretical model for news sharing that includes all communication channels, both "old" and "new."

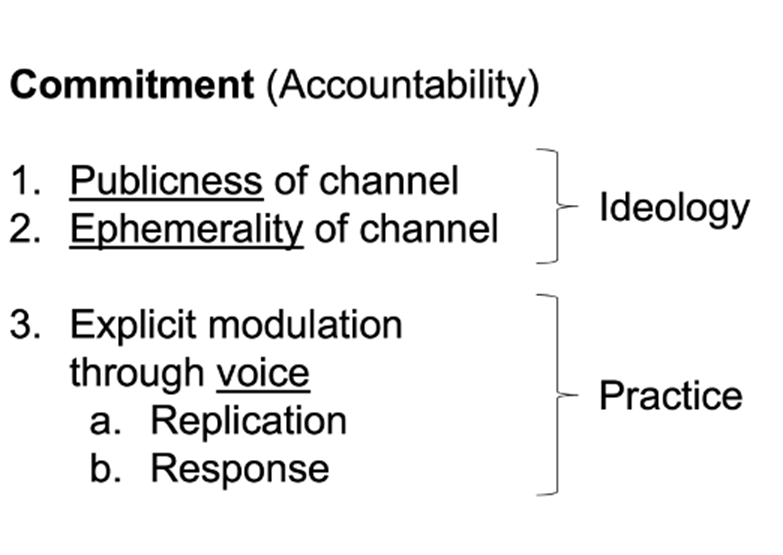

The paper is informed by Knology's long-standing partnership with PBS NewsHour, including extensive data collection with news users and journalists alike. Dr. Barchas-Lichtenstein's model centers on the relationship between commitment (roughly, willingness to be held accountable) and sharing news. By default, news sharing requires commitment, and the model highlights three ways of dialing commitment up and down: publicness , ephemerality , and voice.

As can be seen above, the first two of these variables are ideological—that is, they have to do with perceptions of particular media channels. Both publicness and ephemerality inform our levels of commitment, and thus influence our news-sharing decisions. By contrast, voice is something that people control more actively. It's a matter of practice, and is something we can use to consciously dial up or dial down our levels of commitment. Here's how these variables interact in the model:

Publicness

Sharing something more publicly is understood to require more commitment than sharing it more privately. Interestingly, there are consistent shared understandings about particular communication channels being more "public" or "private"—even though these understandings have little to do with the technological aspects of those channels. For example, even though we generally consider text messages to be private, this is frequently not the case (as anyone familiar with the public release of Mark Meadows' text messages would be able to tell you). To give another example: we might believe that email is private, but employers typically own email accounts used for work purposes (as anyone who has gotten in trouble for complaining about bosses on corporate email would know).

Ephemerality

Similarly, ephemerality (that is, how long the communication is assumed to be accessible) is linked to commitment. Like publicness, this is also not an objective attribute of a communication method. For example, people in the US tend to think of speaking as less ephemeral than writing—but a written grocery list is far less likely to be reviewed later than a speech given in public. And almost any communication could resurface later, far from its original context.

Voice

Finally, individuals use voice (that is, their commentary, which is not necessarily spoken) to modulate the extent of their commitment to the story being shared. Barchas-Lichtenstein highlights two modes of voice: "responding to" the content or "replicating" the content. Cutting out a story from a newspaper and sending it to a friend would be an example of "replicating" content, whereas doing this with some commentary attached to the story (for example, in the margins of the text) would constitute a "responding" mode of voice. People sometimes offer explicit commentary on news content, and sometimes treat news content as if it speaks for itself. "Responses" allow people to make their commitment explicit, while "replications" take commitment for granted.

Let's Put it to Work!

When you get right down to it, there's not really much difference between sharing a cut-out newspaper story with someone and sending them an internet link to that story via text message. The idea that the "share" button constitutes a radical break with earlier ways of sharing news media content is erroneous; whether we're dealing with "old" or "new" communication channels, our decisions about sharing are shaped by the same things—as are the ways we dial commitments up or down.

Here are some practical suggestions for putting Barchas-Lichtenstein's model to work.

For Researchers

- Be skeptical about claims that any technology represents a radical break with the past

Instead of assuming that social media has created a totally different landscape of media sharing, examine the evidence upon which these claims are made; - Study media sharing behavior in a variety of different contexts

Instead of confining explorations of this topic to social media platforms, consider how online media sharing behaviors compare to offline practices (for example, people sharing newspaper articles with each other on the subway).

Funding

The data discussed in this paper were collected with support from the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 15163471 and 1906802, and the National Institutes of Health under Grant No. #1R25OD0202212-01A1. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or the National Institutes of Health.

References

Pew Research Center (2022, September 20). Social Media and News Fact Sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/social-media-and-news-fact-sheet/

Photo by Peter Lawrence on Unsplash