A Framework for Building Trust

Knology's model for building, maintaining, and restoring trust

Trust is a key component of healthy relationships. In a time of growing distrust in our institutions, our communities, and even each other, it’s important to invest in practices and strategies that can build and maintain this vital commodity—and rebuild it when it’s been lost. Through our work on trust (which includes peer-reviewed publications, research-to-practice briefs, critical reflections, conferences,, and projects), we’ve found that whether considered in the context of interpersonal relationships, relationships between organizations and their audiences, or even interactions with non-human agents like artificial intelligence (AI), all trust-building efforts need to begin with the same question: how do I become trustworthy?

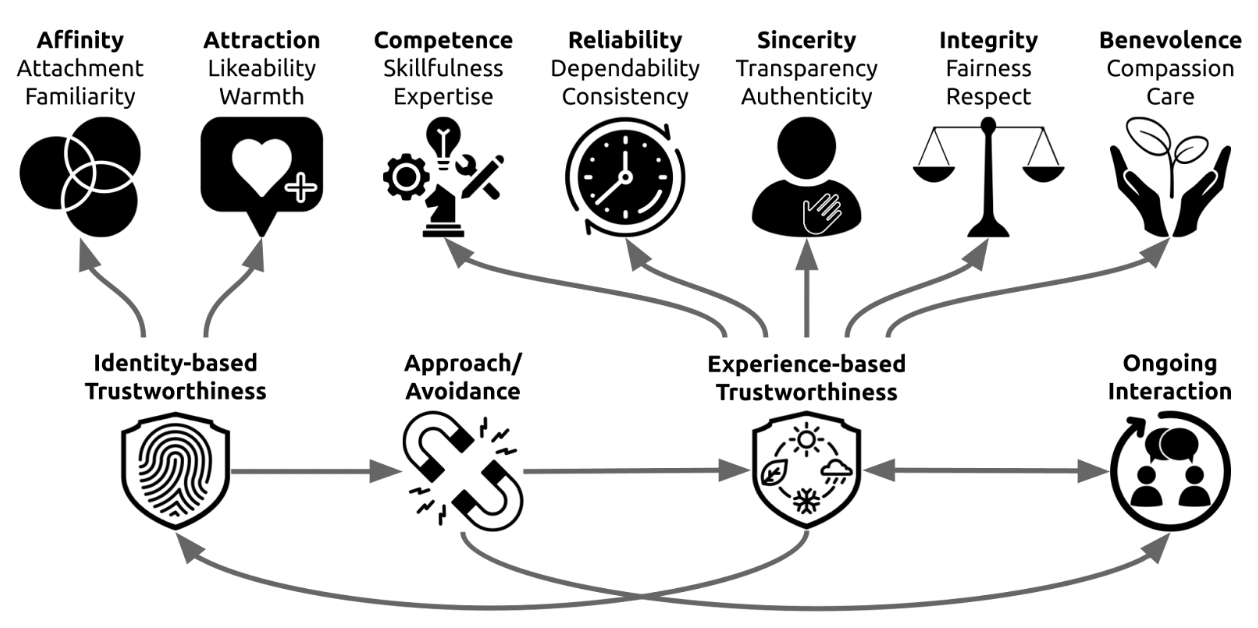

In response to this question, we’ve created a framework for building trust. Our model highlights the intersections between two forms of trust: identity-based trust and experience-based trust. In this blog post we unpack our trustworthiness model, showing how its component parts fit together and discussing how it can be used to create trusting relationships.

Our Trustworthiness Model

Through decades of research, psychological and behavioral scientists (as well as philosophers) have learned that there are two primary types of trust — one called “identity-based trust,” and a second called “experience-based trust.” As can be seen below, our model encompasses both of these and highlights the role that their different components play in determining the level of trust we place in others.

Identity-Based Trust

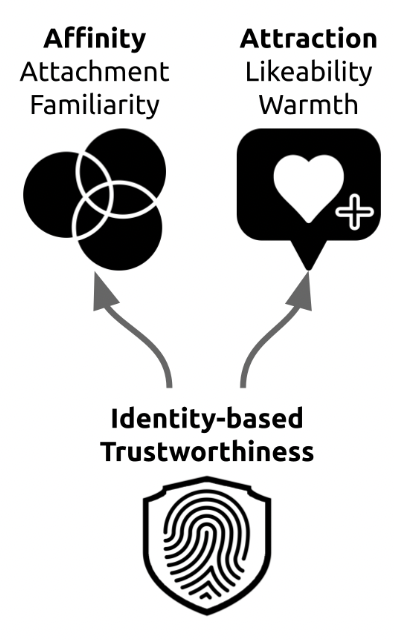

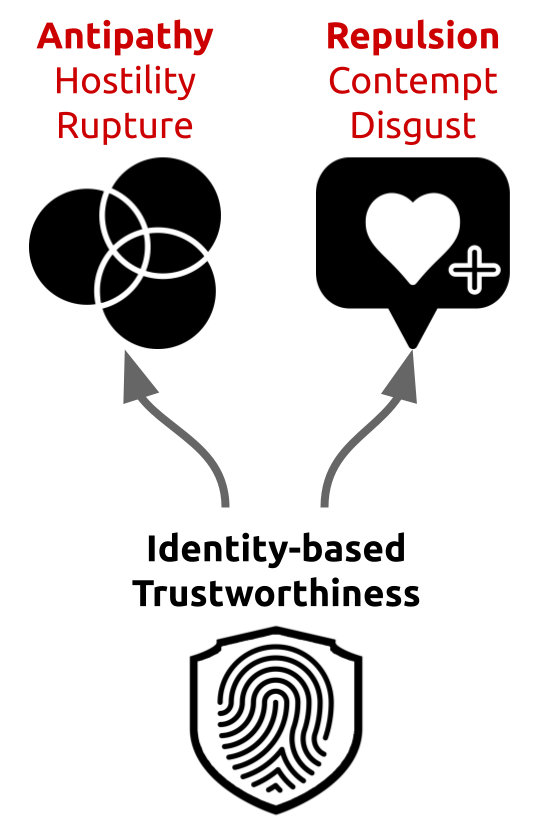

Identity-based trust is established through feelings of attraction and affinity. It’s what happens when we feel that another person appears friendly or seems similar to us. It’s usually established prior to any actual interactions with that person, and convinces us that they are worth approaching and engaging with. By contrast, if we haven’t established identity-based trust with someone, then we’re more likely to avoid them. In other words, identity-based trust is useful in helping us resolve approach/avoidance questions.

Identity-based trust is established through feelings of attraction and affinity. It’s what happens when we feel that another person appears friendly or seems similar to us. It’s usually established prior to any actual interactions with that person, and convinces us that they are worth approaching and engaging with. By contrast, if we haven’t established identity-based trust with someone, then we’re more likely to avoid them. In other words, identity-based trust is useful in helping us resolve approach/avoidance questions.

As noted in our model, affinity includes feelings of attachment. In interpersonal relationships, attachment has to do with how comfortable we feel relying on others for support and security. In organizational settings, attachment is often referred to as “psychological ownership” or “perceived insider status.” It’s what happens when we feel a sense of possession toward an organization — in other words, when we feel that organization is ours. It occurs when we feel an organization reflects our core values or our individuality. Because of that, in institutional contexts, attachment is sometimes also simply called “belonging.” Attachment also factors into human-machine interactions. Here, attachment has to do with whether the human desire for companionship — especially in stressful circumstances — might be fulfilled by inanimate objects like robots or AI.

Experience-Based Trust

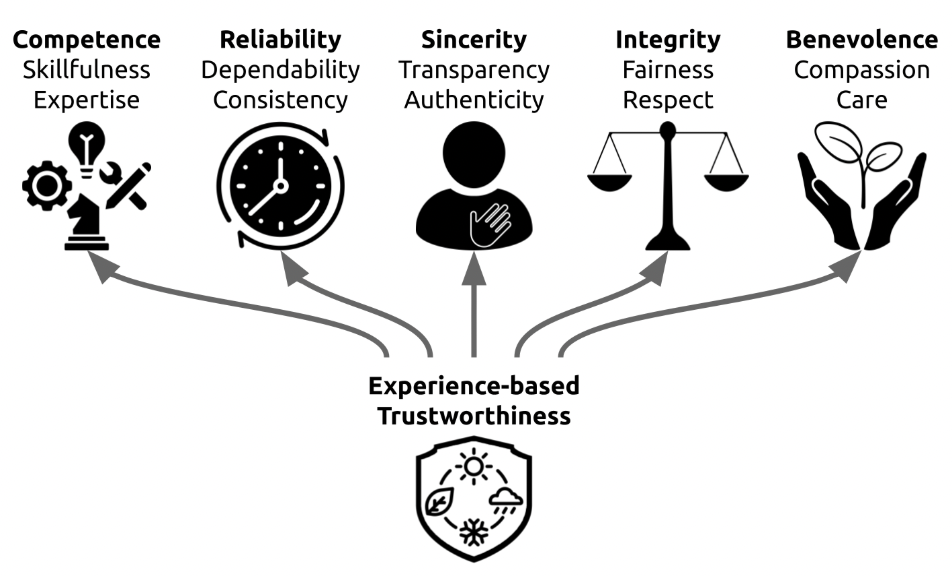

Experience-based trust comes into play after we’ve resolved questions about identity-based trust. It’s the form of trust that’s established through judgment of another’s behavior. It’s what happens when our interactions with someone or something have been positive and led to good outcomes. Assessments of experience-based trust are generally based on our answers to five key questions:

Experience-based trust comes into play after we’ve resolved questions about identity-based trust. It’s the form of trust that’s established through judgment of another’s behavior. It’s what happens when our interactions with someone or something have been positive and led to good outcomes. Assessments of experience-based trust are generally based on our answers to five key questions:

- Can you do what you promised? (competence)

- Do you deliver on your promises? (reliability)

- Do you appear honest and transparent about your abilities and limits? (sincerity)

- Do you appear to act in a principled manner, and apply your principles equitably across different audiences? (integrity)

- Do you know and appear to care about the needs of different audiences? (benevolence)

The Process of Building Trust

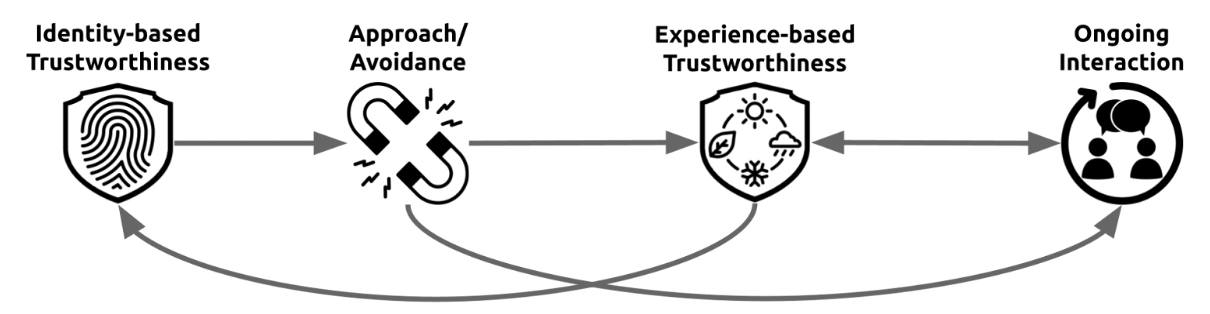

Trust is not static. It’s an ongoing process. The levels of trust we place in others are constantly being updated on the basis of our observations and interactions. Moreover, identity- and experience-based trust can impact each other.

Our model presents an understanding of how trust changes over time. As shown above, trust is usually first established through identity-based criteria. Something about another’s identity convinces us to engage with them. In an organizational context, identity-based trust is what gets audiences in the door—it’s the feeling that the institution is fun or friendly or familiar in some way. The presence of identity-based trust encourages individuals to approach the institution. From there, evidence from our interactions is used to make determinations about experience-based trustworthiness. If this is established, then often, the result is long-term engagement (for example, deciding to purchase a membership or enrolling in a subscription-based service).

Our model takes into account the intersections of identity- and experience-based trust. The two forms of trust do not exist on separate tracks. Instead, they impact each other. At the beginning of a relationship, when we have little experience to inform our trustworthiness assessments, we tend to base them on identity. But identity-based judgments can be reassessed in light of our experiences. For example, if experiential trust is lacking or broken, this can negatively impact assessments of identity-based trust—such that initial feelings of affinity and attraction may transform into their opposites (that is, feelings of antipathy and repulsion).

Our model takes into account the intersections of identity- and experience-based trust. The two forms of trust do not exist on separate tracks. Instead, they impact each other. At the beginning of a relationship, when we have little experience to inform our trustworthiness assessments, we tend to base them on identity. But identity-based judgments can be reassessed in light of our experiences. For example, if experiential trust is lacking or broken, this can negatively impact assessments of identity-based trust—such that initial feelings of affinity and attraction may transform into their opposites (that is, feelings of antipathy and repulsion).

Scholars refer to this process as "disidentification," and it occurs when individuals reject existing connections with others in response to perceived violations of experience-based trust criteria.

Let's Put it to Work

Trust is how we deal with our inability to survive without others’ help. As a social species, trust is something that we’re hardwired for. Yet even if the willingness to place ourselves in others’ hands is an innate human trait, the process of establishing and maintaining trust often takes time and effort. It’s a reflection of both our identities and our experiences, and it is constantly being updated as we receive new information about ourselves, others, and the world around us.

Given this, it may seem daunting to balance all of the different elements of trustworthiness at once. But reflecting on the framework can help people and organizations identify areas where they are already doing well—and aspects of trustworthiness they may need to work harder to demonstrate. The areas that are most relevant, along with specific strategies to address them, depend on context. For example, we've found that children's museums prioritize showing affinity, integrity, and benevolence towards their audience.

Our current Culture of Trust research project will develop recommendations for museums working through contentious issues internally, based on the aspects of trust these interactions call into focus. A key goal of this project is to help museums devise specific trust-building practices and strategies that can help leaders and staff navigate discussions of contentious issues.

As all of this suggests, our trustworthiness model is a starting point, not a final destination. In and of itself, the model doesn’t offer any concrete suggestions for establishing, maintaining, or repairing trust. What it does offer is a pathway to understanding which aspects of trust matter most in particular contexts, along with a process for measuring the impact that particular actions have on trust. The knowledge that emerges from use of the model can contribute to the creation of trusting relationships between individuals, between organizations and their audiences, within communities, and even between human and non-human actors such as AI.

About this Article

Want to learn more about trust? The best place to start is our “Trust 101” primer. From there, take a look at our work on why benevolence is key to our perceptions of trustworthiness, our research into how people assess the trustworthiness of zoos and aquariums, a conversation about the role of trust in public health, some findings pertaining to the role of partnerships in trust-building, and our thoughts about how moral motives factor into considerations of trust and trustworthiness. Be sure to also check out emerging findings from our “Culture of Trust” project.

Photo by Alex Shute @ Unsplash