Building Trustworthy AI

To understand how AI can effectively promote computer science learning, we first need to learn about what influences perceptions of AI trustworthiness.

A recent article in Nature proclaimed that AI is coming to science education, “ready or not.”

In many computer science (CS) classrooms, teachers have begun adopting AI-based tools like ChatGPT to help write lesson plans, prepare content summaries, and generate ideas for research projects. Their students are also using these tools to complete assignments and enhance their programming proficiencies. Studies show that using AI coding assistants (including OpenAI Codex, DeepMind AlphaCode, and Amazon CodeWhisperer) can positively influence student CS learning — both in terms of helping solve problems and providing personalized, real-time explanations to aid understanding of programming concepts (though outcomes are sometimes mixed and may be dependent on using specialized models).

For novice learners, AI tools are especially valuable. Introductory-level CS courses have a steep learning curve. Many first-year students perceive CS to be difficult, and they confront a variety of barriers to learning—whether in connection with specific tasks like identifying and explaining syntax errors or more general problems like writer’s block (that is, not knowing how to get started, or how to continue once stopped). Beginners see automated help as an attractive way to overcome these barriers, and appreciate the way AI coding assistants can offer a form of homework help. And the evidence suggests that these tools can be effective learning companions: One recent study found that the use of AI coding assistants can reduce stress and discouragement in computer science learning, helping students persist through difficult tasks and achieve at higher levels.

AI and the Challenge of Trust

Despite these benefits, the use of AI in CS classrooms presents both opportunities and challenges. A key difficulty is that AI-suggested solutions are sometimes incorrect. This problem of false answers is a particularly acute one for novices, who may rely too much on auto-generated responses, and who may not always be able to verify the accuracy of those responses. For altogether logical and laudable reasons, when misled, these students may lose trust in the feedback provided by AI tools. As one study puts it:

Misplaced trust in a misleading response can lead to long-term learning obstacles, particularly for novice learners still building their understanding of the concepts…[F]uture work should focus on developing adaptive tools that facilitate effective use of AI-generated outputs, aligning student trust with the veracity of the AI-generated responses…This way, we can pave the way for a more trustworthy and productive AI-assisted learning experience.

As this suggests, students’ willingness to use AI is largely determined by the amount of trust they place in this new technology. But within the classroom context, students’ assessments of AI trustworthiness will also be informed by their teachers’ own attitudes toward AI. Given that a significant part of what teachers do is influence their students, it is likely that teachers’ views as to whether or not AI is trustworthy will (at least partially) shape students’ own views. So too will students’ perceptions of their teachers’ trustworthiness shape their own views on AI.

In other words, the level of trust CS students place in AI is shaped by three different relationships: (1) their relationships with their teachers; (2) their teachers’ relationships with AI; (3) their own relationships with AI. The reason for that is that interactions with AI in educational settings are a form of “testimonial learning.” Understanding why this is so is critical to building trustworthy AI.

AI and Testimonial Learning

Testimony—that is, things we hear from other people through social interaction—is one of the main ways we acquire knowledge about the world. Whether it be a bit of news conveyed by a reporter, an update on our health communicated through conversation with a doctor, or information about a broken-down car conveyed by an auto mechanic, we are constantly engaging in testimonial learning. In the first years of our lives, we learn on the basis of testimonies shared by parents and caregivers. Later on, teachers become a primary source of testimonial learning.

Importantly, this is not a passive process. Testimonial learning involves a back and forth between speakers and listeners. When providing their testimonies, speakers try to convey reasons for believing them. Listeners question these reasons, and demand to know why they should accept what the speaker is saying. Learning only happens when these questions and demands are satisfactorily met. Another way of saying this is that testimonial learning is a reciprocal process of learning to trust and trusting to learn.

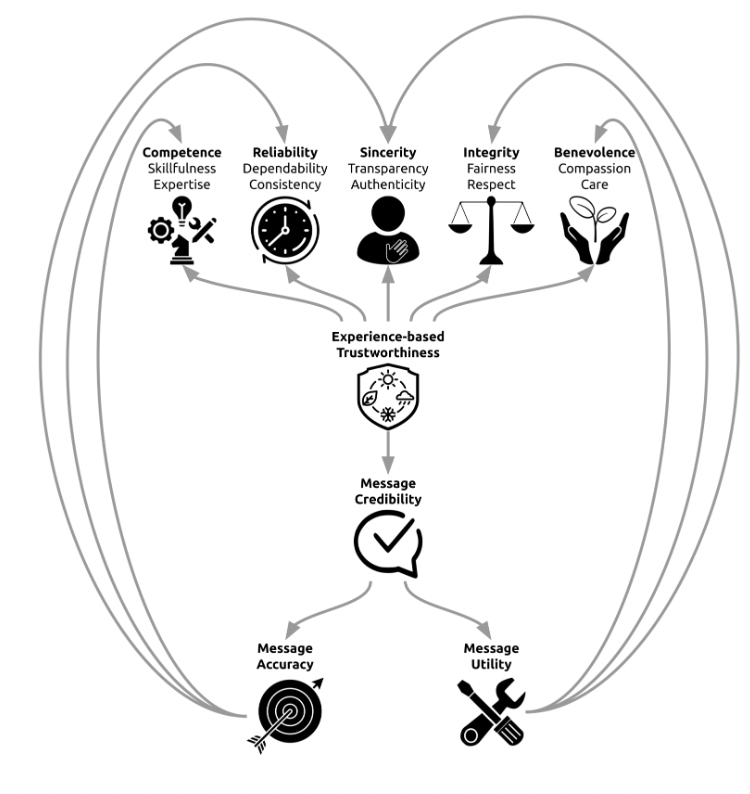

Like other providers of testimonial learning, AI is arguably an “expert". Even though AI tools possess neither personality nor moral values, their ability to generate code and explanations with a high level of accuracy gives them a classroom role akin to that of a tutor. Practically speaking, what this means is that when assessing the trustworthiness of an AI coding assistant, students will use the same criteria they use to evaluate teacher trustworthiness—namely, the experiential criteria of competence, reliability, sincerity, integrity, and benevolence.

A Model for Building Trustworthy AI

The model below expresses the different kinds of assessments that factor into decisions about whether or not to trust AI. As the model indicates, assessments of AI trustworthiness revolve around considerations of message accuracy and utility. If the information we receive from AI tools proves correct, then we are more likely to see these technologies as competent and reliable (the cognitive aspects of experience-based trust). Novices would need to be reminded (either by the AI assistant and/or the teacher) to test the code that AI generates.

Much of the research on trust and AI focuses solely on message accuracy. But utility is of equal importance. If we are to develop a trusting relationship with AI technologies, we need to be convinced that the information we are receiving is not just accurate, but also useful. Utility strongly relates to benevolence and integrity (the moral aspects of experience-based trust). If the answers we get from AI tools are useful, we begin to think that these tools are acting with our best interests at heart. For example, by following an empathetic script, AI tools can behave in a respectful, caring manner (even if this is only the appearance of benevolence). Empathetic scripts can be designed to not only probe users’ levels of understanding, but also to build up their confidence, inquire into and support their physical and emotional states, and incorporate users’ preferences into their responses. All of these behaviors can contribute to heightened perceptions of AI trustworthiness.

Sincerity is also an important criterion for evaluating the trustworthiness of an AI. Both message accuracy and utility factor into this. When an AI reminds users of its limitations, of the fact that it is only an algorithmically-driven machine, and of the possibility of generating hallucinations, then users will be more likely to see it as honest. This assessment will inform decisions of whether and how much to trust the AI.

Let's Put it To Work

The design of AI assistants for CS students should take into account all five components of experience-based trust. At present, the extent to which each of these components shape perceptions of AI trustworthiness is unknown. By exploring their impacts on trust, we’ll be better positioned to design effective AI learning companions for CS students.

In an educational context, the starting point for this exploration should not be human-machine interactions themselves, but instead, the role that trust plays in classroom-based collaborations between students, teachers, and AI coding assistants. If these collaborations build trust, then the likelihood that AI serves as a helpful learning tool increases. If not, then AI tools will struggle to live up to their full potential. By studying the three-part relationships between students, teachers, and AI coding assistants, we can construct trust profiles—including those that highlight instances of overreliance and over-trusting. With these profiles, we will be better positioned to design more trustworthy instructional AI, the effects of which will be seen not only in the computer science field (which has long struggled to recruit a sufficient number of qualified professionals), but also throughout society more generally.

About this Article

Want to learn more about our trust research? The best place to start is our “Trust 101” primer. From there, take a look at our work on why benevolence is key to our perceptions of trustworthiness, our research into how people assess the trustworthiness of zoos and aquariums, a conversation about the role of trust in public health, some findings pertaining to the role of partnerships in trust-building, and our thoughts about how moral motives factor into considerations of trust and trustworthiness.

Photo courtesy of Artturi Jalli @ Unsplash