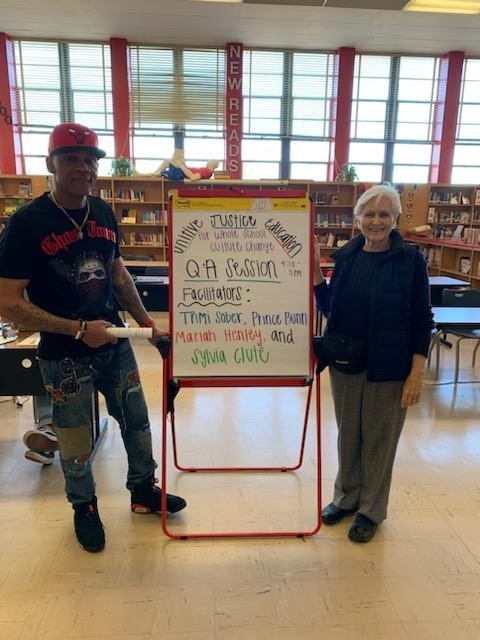

Spotlight on: Sylvia Clute, Alliance for Unitive Justice

This edition of the Searching for Justice series profiles the work of Sylvia Clute.

Around 2 million people are incarcerated in the United States at any given time (Sawyer & Wagner, 2020; Vera Institute, 2021). When they are released, most of those people will face "invisible punishment" (Travis, 2002) such as community supervision requirements, fines, and the denial of voting rights. Unfortunately, news media coverage of the difficulties of reentry has some major gaps. To fill these gaps, the Kendeda Fund is supporting PBS NewsHour's Searching for Justice series, along with Knology's independent work to convene experts who are providing formative feedback on the series. We're amplifying those experts' voices and their work through a series of brief profiles.

*

What does it mean to practice justice as love? This is a key question for Sylvia Clute, whose goal is to systematically transform society's relationship to discipline and punishment. When Sylvia entered law school, there were still quotas limiting the participation of women and racially minoritized people in the field. Sylvia was told that our traditional justice system was the best that could be designed. At that time, she says, she did not yet think to ask a crucial question: Best for whom? Then after law school, Sylvia found that she could not get an interview at a law firm. The reason? "Clients wouldn't want to be represented by a woman," one interviewer told her. Resigned to being excluded because of her gender, Sylvia started up her own solo practice in Richmond, Virginia, and decided to focus on fighting against systemic inequality. It was 1975, the height of the women's movement, and she got involved, both to find worthwhile cases she could take on in her practice and because it was what her heart led her to do. At the time, Virginia had many common law rules relating to women and racially minoritized people, including laws that restricted the rights of married women. And Sylvia, as one of the few female attorneys in Richmond, got busy working to change those laws.

*

Years later, while interviewing an associate for her firm, Sylvia learned about a book that would set the stage for her work today. A Course in Miracles was not an easy read the first time through, but it explained the justice system in a way that spoke to Sylvia. What it said was that there are, in reality, two models of justice: vengeance and love. Sylvia knew what justice as vengeance was. That's what she offered her clients. But she "didn't have a clue what justice as love would be" or how one would go about implementing it. It was then that Sylvia decided she would do whatever it took to find out.

*

Today, 36 years after beginning what she describes as a "journey" toward a new understanding of justice as love, Sylvia knows exactly what this means. She calls it "Unitive Justice" (a term she coined): a model of justice that rejects the common (and antiquated) idea that the punishment should fit the crime. That is, instead of an "eye for an eye" system, which assumes that justice must be punitive, Sylvia asks whether we can envision and put into practice a new moral premise for the justice system. She calls this premise " lovingkindness." Such a system would refuse to compound harm through punishment. Instead, it would address the harm that's been done by discovering the root causes and healing it.

Sylvia tells me that if you had to narrow Unitive Justice down to one moral premise, it would be the refusal to compound harm. Unitive Justice recognizes that punishment, rather than reducing harm, may often amplify it. As Sylvia explains, this is due to the justice system's principle of "proportional revenge," where a crime automatically calls up a certain level of punishment. If the crime is repeated, the punishment is escalated. This escalation in punishment creates a moral dilemma, where revenge ultimately becomes disproportionate to the crime being punished. Such a system, Sylvia says, is inherently flawed.

So, how does a Unitive Justice model work? As Sylvia explains, Unitive Justice is successful in decreasing conflict and violence in part because it is focused not only on individual behavior change, but also on system change. Put another way, instead of trying to change individuals' bad behaviors by inflicting punishment on them, the Unitive Justice model also focuses on addressing the basic structures and conditions that lead to conflict. By addressing conflict's underlying conditions, Unitive Justice simultaneously discourages violence while encouraging individuals to self-govern.

But Unitive Justice is more than just a theory. According to the data collected from schools that have been implementing the model, Unitive Justice is also incredibly successful in practice. The case in point is Armstrong High School in Richmond, Virginia, where Sylvia's team set up shop from 2011 to 2013, teaching faculty and students how to implement a disciplinary model of Unitive Justice. According to statistics from the Department of Education, the total number of behavioral incidents in the 2010-2011 school year, before Unitive Justice came to Armstrong, was 583. In the program's second year, 2012-2013, this number plummeted to 150, one-fourth as many incidents. Incidents against staff also went to one-third their previous level. Ultimately, the total number of students involved in conflicts was less than half of what it was before Sylvia's team came in.

One example of how the difference between punitive justice and Unitive Justice plays out in practice is through schools' "No Contact" contracts. When two or more students are involved in a conflict, schools may require them to sign a contract agreeing to have no verbal or physical contact. This practice fits within a punitive model of justice, which separates individuals in conflict, rather than searching for ways to bring them back together in reconciliation. As a result, Sylvia says, additional conflict often ensues. In the case of schools, isolation breeds more conflict. When students remain separated, they are more susceptible to the rumors, inflammatory comments, and bad information that other students (especially those who wish to prolong the conflict) might spread. As a result, the initial conflict may escalate and prevent any chance of reconciliation. In contrast to this isolation model, which is also used in prisons, a Unitive Justice model does not force individuals to separate but instead gives them the option of a different kind of contract. This agreement, which is optional, asks students to come together around a unified goal. The goal, which is defined by the students in conflict, may be reconciliation, renewal of the friendship, or something else. United around a shared objective, the students become less vulnerable to outside influence and more focused on mutual healing or, like Sylvia says, on practicing justice as love.

*

Unitive Justice, or justice as love, is a path toward repairing the flaws in our current system. And while Sylvia says that it is not meant to completely replace punitive justice, it is meant to exist as a parallel system, which is available as an option anyone may freely choose to take. After all, Unitive Justice is inherently about self-governance and encouraging individuals to choose for themselves whether they wish to be punished, or heal. The goal, however, is that Unitive Justice continues to make its way through schools (and potentially into prisons) both to heal past and present wounds inflicted by the school-to-prison pipeline and to render traditional punitive systems less and less relevant.

Sylvia is currently working with colleagues Paul Taylor (click here for our spotlight on him!) and Prince Bunn, both of whom were formerly incarcerated, to develop a training program that aims to remake prison culture in the image of Unitive Justice. The program currently contains 18 lessons and is continuing to evolve. Sylvia also envisions Unitive Justice making its way into other contexts, like churches and workplaces, where the public can learn that they have a choice to practice justice as love. In October 2023, Sylvia's team will be hosting the first ever Unitive Justice International Conference. The conference proceedings will be made public online for anyone who wishes to learn more about Unitive Justice and its role in transforming the criminal justice system, education, and other areas. Beyond the United States, Sylvia's model has now reached Uganda, where a school is currently being built around the concept and practice of Unitive Justice. "We want people to know that we can do something different," Sylvia says. And that's what Unitive Justice is all about - knowing we have the option to repair our broken systems and, in doing so, to build a less vengeful and more loving world.

Cover Image: Tingey Injury Law Firm on Unsplash

Article Photo Credit: Sylvia Clute