Spotlight on: Taylor Paul, Taylor Paul Taylor LLC

This edition of the Searching for Justice series profiles the work of Taylor Paul, a community-organizer and business leader who has founded and contributed to numerous initiatives aimed at giving power back to those who have gone through the US carceral system.

Around 2 million people are incarcerated in the United States at any given time (Sawyer & Wagner, 2020); Vera Institute, 2021). When they are released, most of those people will face "invisible punishment" (Travis, 2002) such as community supervision requirements, fines, and denial of voting rights. Unfortunately, news media coverage of the difficulties of reentry has some major gaps. To fill these gaps, the Kendeda Fund is supporting PBS NewsHour's Searching for Justice series—and Knology's independent work to convene experts who are providing formative feedback on the series. We're amplifying those experts' voices and their work through a series of brief profiles.

*

"Returning citizens shall be described as relevant." That's Taylor Paul's catchphrase. Here's why, in his own words:

A lot of the social ills can't be fixed without us. If my car breaks down, I'm not going to take it to a pediatrician. If my baby gets sick, I'm not going to take them to an auto mechanic. The social ills—whether it's gun violence or poverty or housing discrimination—who better to go back inside [the community] than men that have actually experienced it? Men, in some cases, who were using that gun? What better expert to go inside and cure it?

That philosophy is behind almost everything he does, and he does a lot. He's doing everything he said he would do when he left prison, and then some.

*

There's the RVA League for Safer Streets, a local basketball league he started with Jawad Abdu while both men were incarcerated. As Paul puts it, the two men started planning the league when they only knew they'd come home "one day," but not when. They wanted to "eradicate some of the social ills we helped create in so-called 'high-crime' areas" in Richmond, VA. The basketball league includes teams from all over the city, as well as the Richmond Police Department. Basketball, he tells me, is just "bait": it's a way to bring together people from around the city to neutral ground ("where people know they're going to leave the same way they came") to engage in something they all love. It gets them to attend workshops on conflict resolution, problem solving, and critical thinking. Perhaps more importantly, it gets them to realize they share a common interest.

The big shift, Paul tells me, was that when guys would see each other around town, they'd identify one another by their basketball team, instead of neighborhood or gang affiliation, and rib each other about their team's scores. Now they want to win so badly, they play on blended teams and get to know each other that way.

The spirit of healthy competition is particularly important when the police are playing. "Nobody wants to go home and say they lost to the PD, so they get everybody's best game." But that's not why Paul wanted the police in the league. Instead, he says, "It wasn't to teach the guys about them, it was to teach them about us. They need to understand what we are like, what we deal with." And it's paid off. When police come out to deal with a call—say about someone *"loitering"*—they're that much more likely to know each other, and treat each other like people.

'Hey, officer, don't you play in the RVA league?' a guy will ask. 'You gotta work on your jump shot.' Nobody gets shot by law enforcement and nobody goes to jail. All because they share the value of basketball.

*

There's SANITY—Standing Against Negative Influence Towards Youth—the counseling and fatherhood group Paul and Abdu started together while incarcerated.

"That perfect an acronym could only come from God," he says.

*

Then there's his venture capital work with De-Carceration Fund. The fund supports returning entrepreneurs (that is, entrepreneurs who have been incarcerated) and non-extractive business models with the goal of giving power back to people the carceral system has taken it away from. The fund's investment committee includes three experienced investment professionals and three impact professionals. Like Paul, all three impact professionals are founders of successful initiatives who have lived experience of the carceral system.

There's his work with Connect Our Kids, which helps reach out to extended family members of children in the foster care system, to identify and stop the foster-care-to-prison pipeline.

He's an equity advisor to White Men for Racial Justice.

And he works for the Department of Criminal Justice Services in Virginia as a community-based organizer. In the wake of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor's extrajudicial killings, he led a series of Courageous Conversations in five Virginia communities, convening community members and law enforcement to speak honestly about what was working and what wasn't. That led to a series of similar conversations that he hosts with incarcerated and newly released people on an ongoing basis.

He also advocates for more individuals than one could count. He takes every call he gets from incarcerated men who say his story gives them hope. He's supported others for parole and probation whenever he can. And those men are doing what he's doing: starting non-profits, moving from "behind the gun to in front of it" in their communities to change the thinking of young men like the ones they once were.

And he's working on a book with Larry Platt, who profiled him for the Philadelphia Citizen.

*

Taylor Paul was born Paul Taylor, but he changed his name "to acknowledge that I was the complete opposite of who people tried to describe me to be."

He went through a paradigm shift when he was incarcerated, and he's far from the only one. Virginia has one of the lowest recidivism rates in the US. This is why he's so committed to the relevance of returning citizens. They're the best people to work with young men, particularly from their own communities. "If we led them wrong once upon a time ago," he says, "perhaps now we can lead them right. We just need an opportunity."

Cover Image: Kylie Osullivan on Unsplash

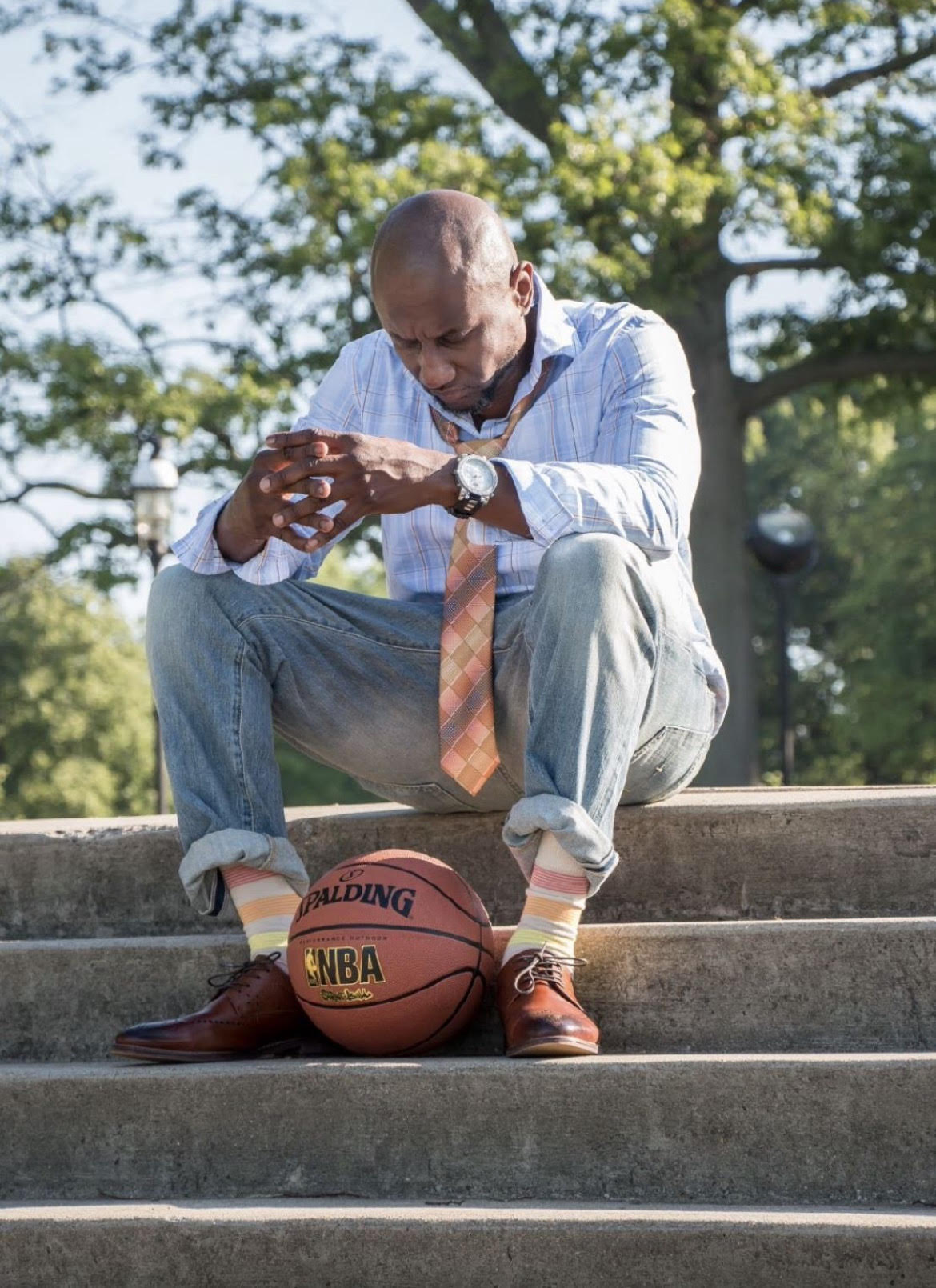

Article Photo Credit: Taylor Paul