Welcoming Patrons with Disabilities in Rural Libraries

How are small and rural libraries addressing the needs of patrons with disabilities?

Small and rural libraries provide essential services to their communities, including internet access for those who may not have a high-speed connection at home, educational programming for people of all ages, and a "third space" for the community to come together for socialization and thoughtful discussion of issues important to them. But for the 1 in 3 adults in rural areas who live with a disability, these libraries are not always accessible.

ALA's Libraries Transforming Communities: Accessible Small and Rural Communities initiative addresses this need through grants for libraries to speak with and better meet the needs of community members with disabilities. So far, ALA has issued 550 grant awards of either $10,000 or $20,000, with 85 libraries receiving two rounds of funding. Currently, 465 small and rural libraries have implemented their accessibility projects or are in the process of doing so. As LTC’s evaluator, we’ve been analyzing reports by the libraries who received funding in order to share what they are learning with the field and provide guidance for other libraries.

Who are libraries focusing on?

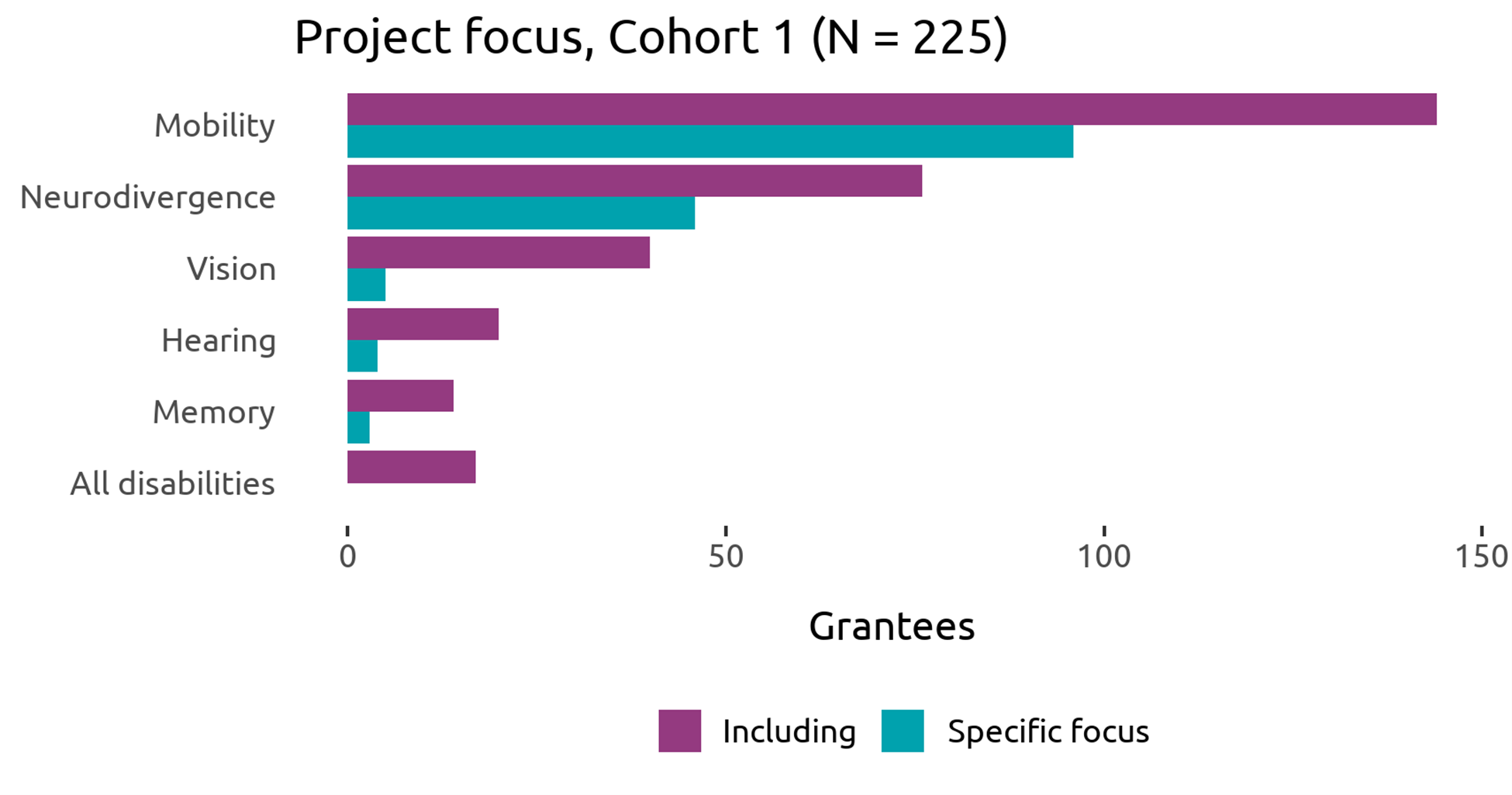

Of the 225 Cohort 1 projects sharing reports with evaluators, 154 focused on the accessibility needs of a specific group, while the remaining 71 worked with community members representing multiple types of disabilities. Based on their discussions with members of the disability communities they were working to serve, the LTC libraries made updates to spaces, collections, and services.

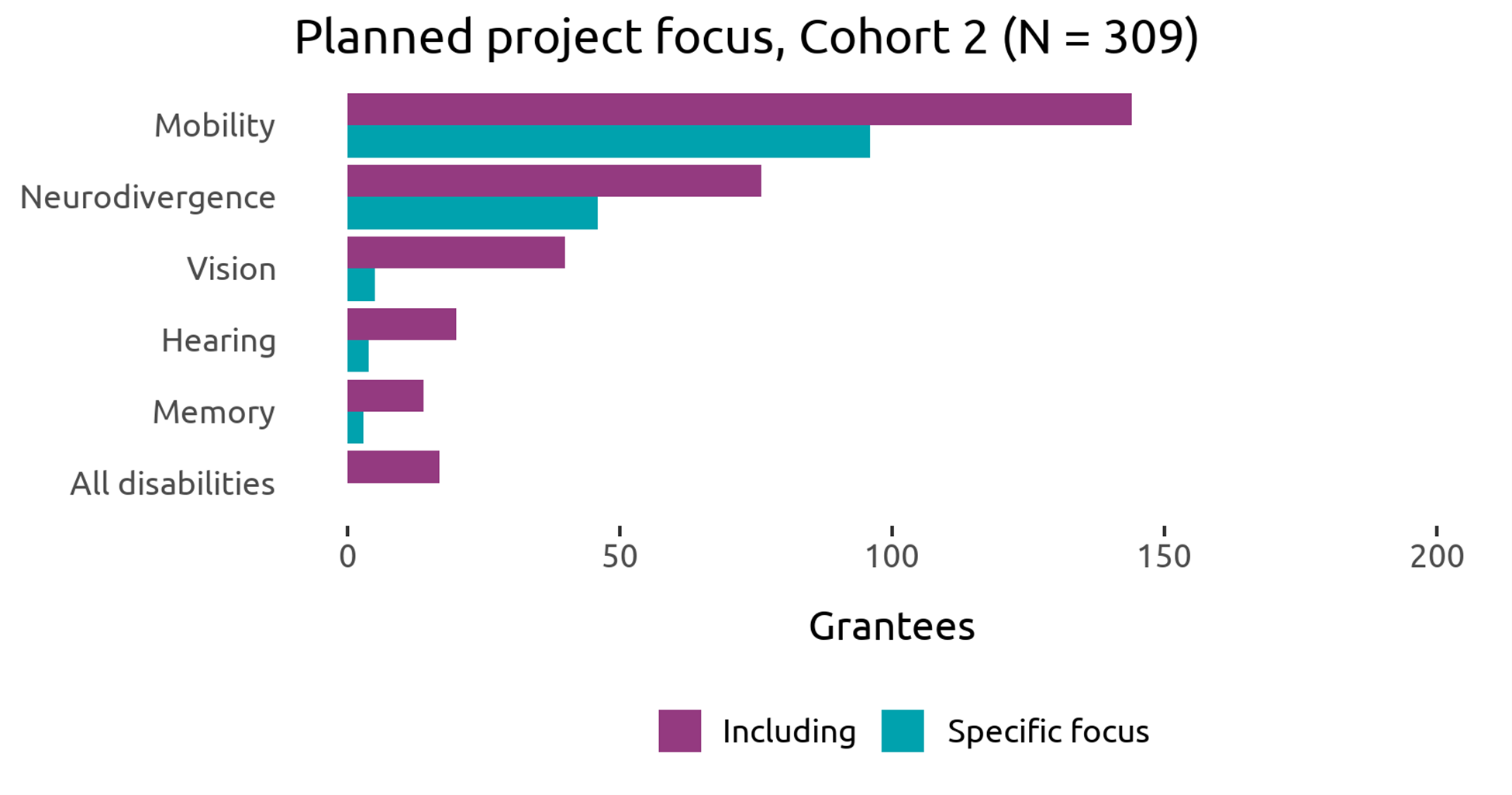

Of the 309 Cohort 2 grantees sharing their application and/or interim reports, 217 projects were planned to focus on one particular type of accessibility needs and 92 on multiple types of disabilities. As in Cohort 1, some Cohort 2 grantees had adjusted their initially proposed projects based on the conversations they had with community members.

Mobility

By far the most common group for grantees to mention working with were individuals with limited mobility, such as people who use wheelchairs or walkers. In many cases, just getting through the door was an obstacle for these (potential) library users, leading libraries to re-pave sidewalks and parking lots outside the building, install or repair ramps, and add button- or motion-activated opening systems to doors. Inside library buildings, common modifications included updated restrooms, chair lifts to move between floors, and adjustable furniture and computer workstations. Other grantees focused on bringing the library outside its building through outreach programming at assisted living facilities or home delivery of collection materials.

Neurodiversity

Libraries working to serve neurodiverse populations tended to focus on sensory needs, both in terms of establishing a comfortable, non-overwhelming space and providing a range of options for sensory exploration and self-regulation. This was the only category where some libraries chose to focus on youth in the target group specifically, and youth-focused initiatives sometimes supported learning differences through investments in educational software, audiobooks or audio-enabled "Wonderbooks," or high-interest/low-reading level books selected based on feedback from teachers and caregivers. Collection materials and programming to support caregivers were also a component of some grants.

Vision

While most libraries did not focus their entire project on blind or low-vision patrons, many were able to make updates to support vision needs. This could involve investments in computers or tablets with screen-reading software or magnifiers for use with physical books. It was also common for libraries to expand their audio and large print collections based on the interests of low-vision patrons. Updated signage and lighting were also part of many libraries' strategies for meeting this group's needs.

Hearing

As with vision, hearing-related library updates tended to be one piece of a wider set of improvements, based on speaking with community members with a range of disabilities. The most common change libraries made based on the feedback of Deaf/hard-of-hearing individuals was installing hearing loops allowing people who use hearing aids or cochlear implants to receive a clearer signal.

Memory

Memory-related needs were brought up in the context of aging, and conversations tended to include caregivers as well as individuals experiencing these conditions themselves. Many libraries including or focusing on these needs added memory kits to their collections, along with programming to engage individuals with dementia and their caregivers (either at the library or an assisted living center).

About this Article

This article is part of a series of blog posts exploring how libraries that received funds through ALA’s LTC: Accessible Small & Rural Communities are working to better meet the needs of patrons with disabilities. In other posts in this series, we look at attempts to put the disability rights movement’s ethic of “Nothing About Us Without Us” into practice, consider efforts focused on neurodivergent patrons and older adults, and look at how small and rural libraries are creating accessible community conversations. You can also read about how these libraries are overcoming challenges to planned accessibility upgrades, building partnerships to address community accessibility needs, and improving patrons’ experiences. Other blogs in this series offer guidance on how to create sensory-friendly programs, how to talk about disability, and how to incorporate accessibility into library strategic planning.

For stories of what individual libraries are doing, see the case studies we’ve published about the accessibility work going on at the Lee Public Library, Jessie E. McCully Memorial Library, Beals Memorial Library, and Bixby Memorial Free Library.

For more on how libraries can become more accessible to patrons with disabilities, see the collection of resources we assembled. And for more information about LTC, see our historical overview of this initiative.

Photo by Robert Ruggiero @ Unsplash