Libraries Transforming Communities

The Libraries Transforming Communities (LTC) initiative seeks to help libraries become community-centered agents of social change.

In 2014, the American Library Association (ALA) launched the Libraries Transforming Communities (LTC) initiative. Undertaken with the Harwood Institute for Public Innovation and Knology (then NewKnowledge), the initiative’s goal is to help libraries “turn outward”—that is, to become leaders and change agents within the communities they serve. By increasing ties with other community institutions (from civic agencies and non-profits to corporations and funders), and helping librarians engage with members of the public in new ways, LTC seeks to help libraries promote positive social change at the local level—especially in terms of civility, collaboration, education, health, and wellbeing.

Since its inception, LTC has gone through four distinct phases of development, all of which have focused on creating and sharing the tools, resources, and other forms of support that libraries need to incorporate community-focused thinking and processes into their work. These phases have been supported by funding from numerous sources—including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), and a private funder.

Throughout the project’s history, we’ve served as the ALA’s research and evaluation partner. Through a combination of surveys, interviews, focus groups, and other quantitative and qualitative research tools, we’ve helped the ALA understand the impact its LTC initiative is having—both on libraries and their communities. In what follows, we’d like to briefly summarize LTC’s history, while also highlighting some of the ways we’ve documented and assessed its impact.

A Brief History of LTC

In the first phase of the program, which lasted from 2014 to 2015, the ALA worked with community-engagement experts to help libraries orient themselves more toward community-focused work. Through a training program and a series of knowledge-sharing sessions, libraries explored the various actions they could take in order to better understand their communities, and to prioritize community objectives in their own work. In all, 10 public libraries participated in the first phase of LTC. For more on their experiences, take a look at how libraries in Columbus, WI, Hartford, CT, Los Angeles, CA, Spokane, WA, and Red Hook, NY, contributed to the first phase of the project.

In our evaluation of the LTC initiative’s first phase (click here for our full report), we found that the ALA succeeded in creating a path for helping libraries more explicitly focus on community engagement.

The second phase of the program, called “Models for Change,” lasted from 2016 to 2019. During these four years, the ALA worked with the National Coalition for Dialogue & Deliberation (NCDD) to create free courses that provided library professionals with tools and approaches for promoting conversation and change within their communities. The partnership, which was funded by an IMLS grant, resulted in a collection of resources designed to help libraries lead “dialogue and deliberation” efforts, with recordings of individual learning sessions posted to YouTube and other free training materials made available through partner websites.

Our assessment of the LTC initiative’s second phase (click here for our full report) showed that the “Models for Change” training materials were well-received by participants, and that the different dialogue and deliberation models (including Conversation Café, World Café, Future Search, and Everyday Democracy) were effective across the three library groups (those serving urban communities, those serving academic communities, and those serving small, mid-sized, and/or rural communities) we examined.

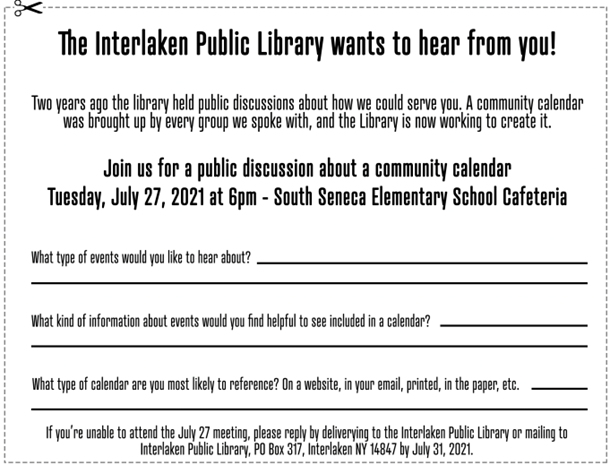

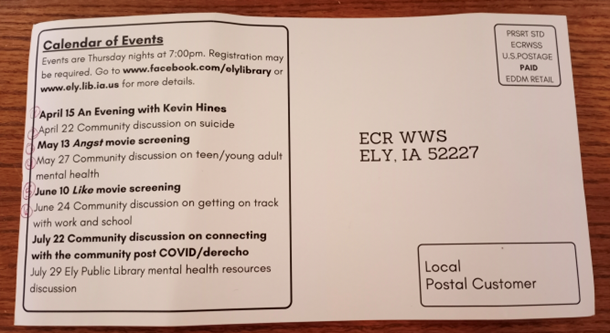

Phase three of the LTC initiative went deeper into explicitly supporting libraries serving small and rural communities. An IMLS-funded project enabled the creation of a suite of resources (including free e-courses and a facilitation guidebook) for helping libraries promote community dialogue. “Focus on Small and Rural Libraries,” which ran from 2020 through 2022 with support from a private funder, awarded $2 million to libraries in support of community engagement efforts. A total of 567 libraries received funding through this program. As we discussed in a series of published case studies, the libraries that received ALA funding through this phase promoted change in a variety of ways: by hosting events geared toward supporting native plants and local wildlife; by initiating discussions designed to give community members an opportunity to provide input on local land development policies; and by promoting discussions of books aimed at helping patrons reflect on difficult subjects such as racism and racial discrimination, food and wellness inequities, and mental health stigmas. Summarizing the impact of these varied efforts, a library worker in Owl’s Head, Maine reflected on how LTC funding “really made the community aware that there is a library and we can function to help the community, [it's] not just a place to come in and get a book.”

In our evaluation of the “Focus on Small and Rural Libraries” initiative (click here for our full report), we found that the training sessions ALA provided were immensely beneficial, as they made library workers more prepared and more confident when it came to facilitating difficult conversations within their communities.

In addition to the aforementioned case studies, we also assessed the broader impact of LTC’s “Small and Rural Libraries” program. In a series of analyses published on the Programming Librarian website (maintained by the ALA’s Public Programs Office), we’ve documented some of the major challenges and obstacles confronting libraries in places with smaller, more dispersed populations. More importantly, our work has also enabled us to see some of the many ways that the LTC initiative is helping library professionals across the country overcome these challenges—whether it be by promoting music lessons and musical gatherings to combat feelings of isolation and disconnection, developing programs and resources that prevent the spread of fake news and other forms of dis- and mis-information, creating more inclusive spaces that are accessible to patrons of all shapes, sizes, and abilities, or using empathy to defuse community tensions and open constructive dialogue around contentious, controversial, emotionally-charged topics. Speaking to some of the ways that these efforts have strengthened communal bonds and promoted community well-being, a library worker who connected patrons to professional mental health resources observed that “It was a way for us to say, ‘Hey, we’re here. We’re listening.’ We have resources and technology to be able to connect people together.”

Next Steps

LTC’s fourth phase was announced in 2022. Called “Accessible Small and Rural Communities,” this will provide more than $7 million to help small and rural libraries make their facilities, services, and programs more accessible to people with disabilities and/or those who are neurodivergent. Grants will be distributed between 2023 and 2025, and will be awarded as either $10,000 or $20,000. To be eligible, libraries will first need to hold input-gathering sessions with members of the public, so as to ensure that efforts to enhance accessibility meet community needs. These conversations will also be used to generate plans for the improvement of library services. Reflecting on this grant’s transformative potential, ALA Executive Director Tracie D. Hall observed that “we have seen what happens when libraries make changes—big and small—that positively impact the ways their communities access and benefit from their services.” Twelve library professionals with firsthand experience of accessibility issues have been chosen to advise this phase of the LTC initiative.

Funding

These materials were produced for Libraries Transforming Communities, a project that has received funding from numerous sources since its inception in 2014—including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, and a private funder. The authors are solely responsible for the content on this page.

Photo by Chris Robert at Unsplash