When Leader-Staff Trust Breaks Down

What an analysis of media stories reveals about leader-staff disputes in museums.

As part of our ongoing Culture of Trust study, Knology is working with our partners at the Association of Science and Technology Centers (ASTC) and the Association of Children’s Museums (ACM) to develop strategies for building, maintaining, and repairing trust between museum leaders and staff when contentious issues enter the workplace.

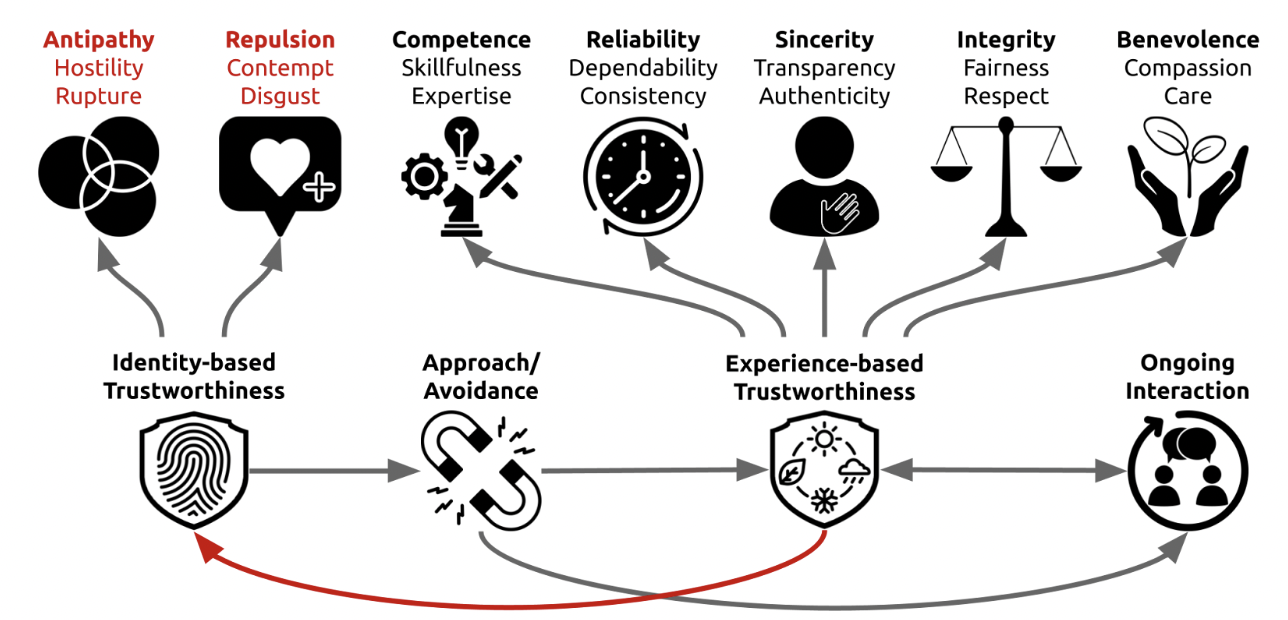

As a step toward this goal, we looked at news media coverage of leader-staff disputes. Analyzing these stories allowed us to identify the components of trust (see figure below) that most often come into play when contentious issues arise in the workplace — and to begin formulating suggestions on how to resolve disputes before trust is completely broken down. Though the situations in the stories we analyzed are exceptional, worst-case scenarios (that is, instances where internal trust was damaged to the point of becoming newsworthy), studying them offers insights on how all museums can build trust between leaders and staff.

What Did We Find?

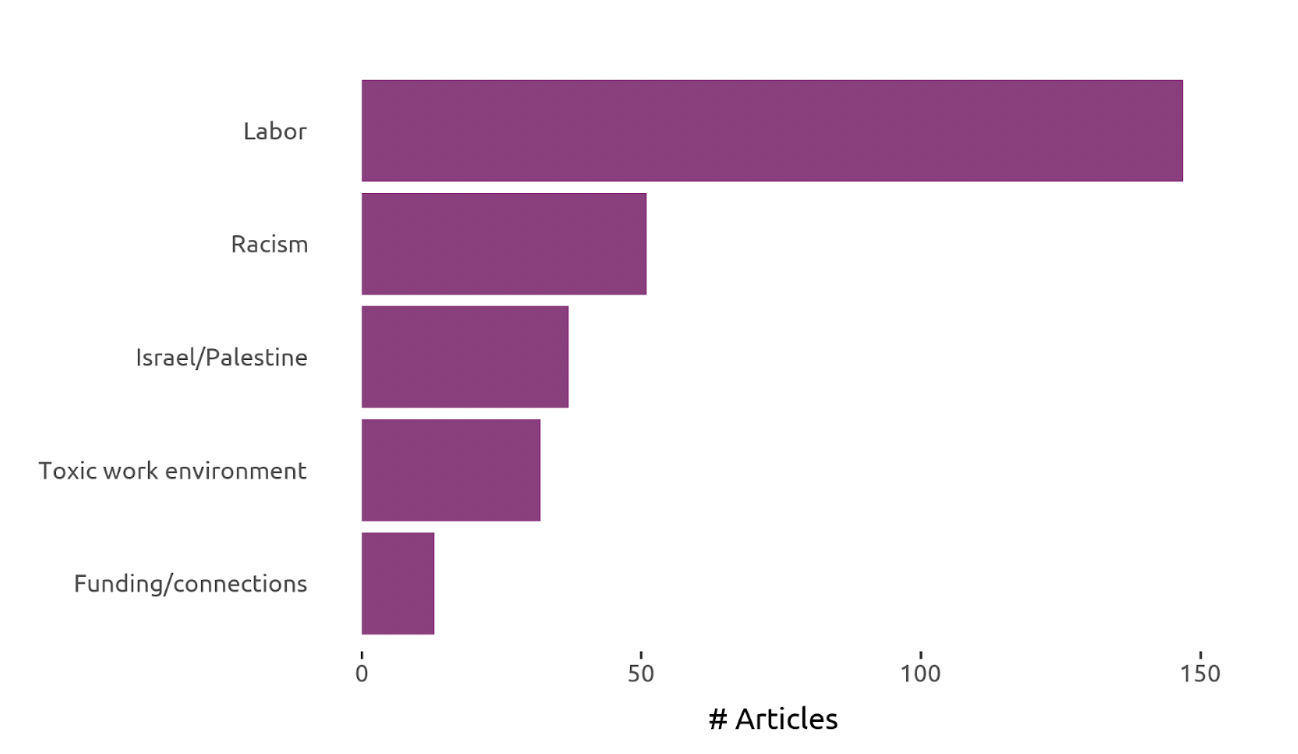

The five most frequent topics of contention in the stories we collected were unionization, racism, toxic work environments, funding sources, and the Israel-Palestine conflict

At the start of our analysis, we identified roughly 300 stories on leader-staff museum disputes published between 2018 and 2024. Most were published after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and nearly all involved art museums. And most disputes revolved around unionization, racism in museum settings, toxic work environments, funding sources (including Board members and other contributors), and the Israel-Palestine conflict. The topics sparking contention reflected broader patterns outside the museum field: for example, Israel-Palestine was an area of contention in museums in 2024, as protests were taking place around the US.

We selected 100 stories for more in-depth analysis (see the "How we conducted our research" section at the end of this post for methodological details).

Museums leaders’ trustworthiness was assessed much more frequently than staff trustworthiness

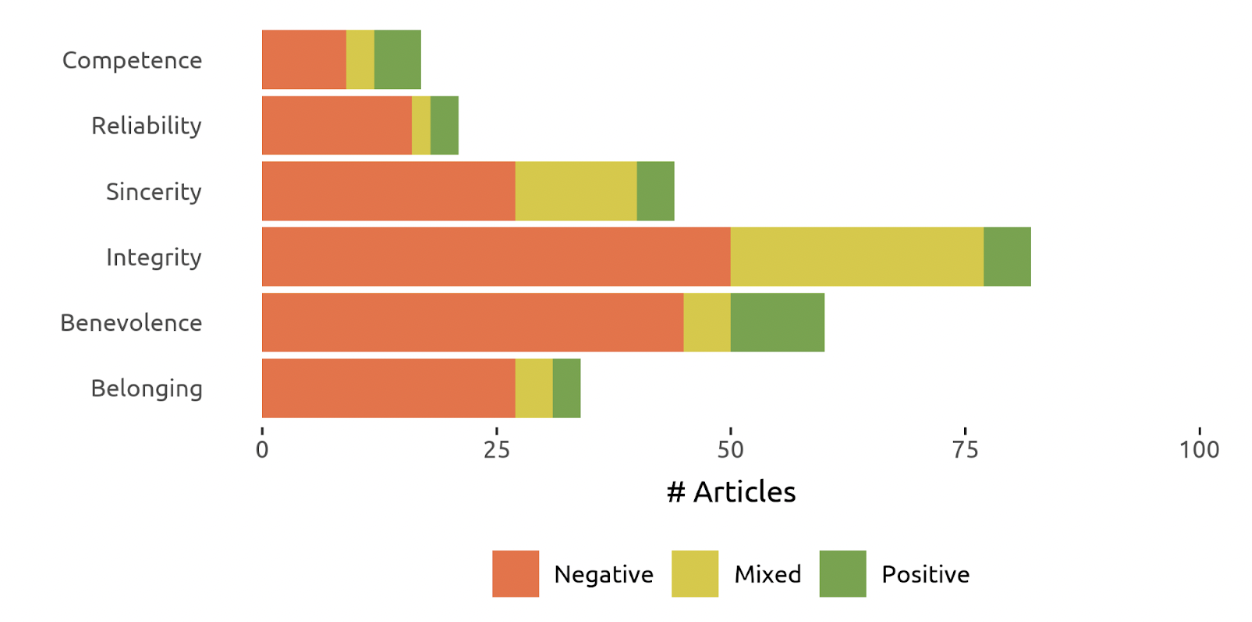

Almost all of the 100 stories we analyzed included an assessment of leadership trustworthiness. As the figure below shows, most of these assessments were negative (shown in orange), although a considerable number were positive (shown in green). For the most part, positive assessments came from museum leaders themselves — typically in response to statements made by staff. Some stories contained both negative and positive assessments (shown in yellow).

Assessments of staff trustworthiness were much less common. And they contained many more positive assessments — most of which came from staff themselves. When leaders were quoted, they generally did not say anything about trustworthiness.

The focus on leader trustworthiness is unsurprising given the fact that internal museum disputes generally only come to the attention of the news media when staff undertake public actions — for example, publishing open letters, or conducting protests and union drives.

Leaders were most often accused of integrity, benevolence, sincerity, and belonging-related violations

No component of leader trustworthiness was assessed more often than integrity — which has to do with perceptions of how fairly others apply their principles. For leaders, most integrity assessments were negative. Example statements from staff included claims that leadership “failed to uphold its own policies” around equity and inclusion, engaged in “censorship,” did not “understand that workers have rights,” or was “complicit in injustices” taking place in the wider world.

Negative assessments of leadership benevolence (that is, our perceptions of whether others demonstrate care for our well-being) were also common. Most claims here focused on alleged mistreatment of staff — for example, that leaders were “emotionally abusive,” that they “exploited the labor, expertise, and care of current staff,” that they demonstrated a “pattern of disrespect and dismissiveness,” or that they had created a “culture of fear.” Claims related to the perceived failure of leaders to provide adequate compensation were also common.

Negative assessments of leadership sincerity (which has to do with perceptions of whether others share information openly and honestly) took a variety of forms. Claims here ranged from a lack of “transparency in institutional operations, acquisitions, and collections” to inauthenticity (for example, “a disconnect between the museum’s actions and its stated mission”) to outright dishonesty (for example, “ongoing efforts…to diminish and inaccurately report to the public and to the museum staff”).

Staff were most often accused of benevolence, integrity, and belonging-related violations

Though assessments of staff trustworthiness were much less common on the whole, leaders sometimes made negative claims related to benevolence, integrity, and belonging. With regard to the first of these, leaders sometimes called staff actions “disruptive,” or alleged that staff had “threatened to undermine the important work [of the museum].”

Positive assessments of trustworthiness were most often (but not always) made when leaders and staff described their own actions

On occasion, staff and leaders offered positive assessments of each other’s trustworthiness. In one instance, staff indicated that removing an abusive director was “the first of many steps in reforming [the museum]” (integrity). In another instance, staff described how leadership had “supported historically marginalized people” prior to the conflict (integrity).

But for the most part, positive trustworthiness assessments came in the form of staff and leaders describing their own actions. Leaders often discussed attempts to address staff complaints. Example statements included claims about how “allegations were taken very seriously and promptly investigated” (integrity), how efforts to address harms had resulted in “much more protection and job security and workplace rights for people” (benevolence), and how leaders were willing to “listen and earnestly engage in dialogue” (sincerity).

At times, leaders framed the same behavior staff objected to as evidence of their trustworthiness. For example, when staff at one museum objected to the lack of an official statement in support of Palestine, leadership responded that "If [the museum] has refrained from lending its voice to any side, it has been so that our many stakeholders can hold theirs” (integrity).

Similarly, positive assessments of staff trustworthiness often came from staff themselves. In some cases, staff defended their competence and reliability before pointing out that their wages had not increased with the cost of living. In another instance, staff made statements asserting their benevolence — for example, “We all love the museum and want it to thrive.”

Let's Put it to Work!

Efforts to preserve and build trust while working through contentious issues should focus on the aspects of trustworthiness seen as lacking. Our media analysis suggests that actively demonstrating integrity, benevolence, and sincerity is particularly important. For example, leaders could demonstrate sincerity by engaging staff in open and collaborative discussions and acknowledging the tradeoffs of each option being considered. The co-ownership of tradeoffs can also head off perceptions of bias or ill will in decision-making (a lack of integrity and benevolence, respectively).

Another important consideration is to be mindful of how decisions may be interpreted. Even when leaders act with all parties' best interests in mind, their behavior may not always be viewed in a positive light. Attempting to rebut claims that trust was violated by asserting good intentions is less effective than demonstrating those intentions in the moment.

Our continuing research will explore concrete actions to preserve trust in the face of disagreements over contentious issues. We have recently completed a review of literature on trust within nonprofit organizations, and an upcoming series of interviews with museum professionals will help us identify strategies and develop resources for successfully building cultures of trust within museums.

How We Conducted Our Research

Search procedures

To identify news stories focusing on internal museum disputes, we searched for articles within Google’s “News” category. This category encompasses a wide variety of sources, including industry-specific outlets such as Hyperallergic and Artnet News (which is where much coverage of museum controversies can be found). Within Google’s “News” category, we examined all results including the words “museum” and “staff” — along with at least one of the following words: “trust,” “controversy,” “protest,” “criticism,” “crisis,” “mistreatment,” “complaint,” “dispute,” “demand,” “toxic,” and “union.” We focused on stories published in the US between January 1, 2017, and October 3, 2024 (the date the search was conducted).

Selection procedures

Initial screening resulted in a list of over 300 potential articles describing events in a total of 115 museums, with most results published in 2020 or later. To select content for analysis, we chose to focus on the most frequently recurring topics of contention—unionization, racism, the Israel-Palestine conflict, toxic work environments, and funding sources—and randomly selected an approximately equal number of articles for each topic. (The topic of funding sources yielded fewer than 20 articles, so additional articles were selected from other areas to bring the total number of articles analyzed to 100.)

Analysis procedures

We then closely read each of the 100 sampled articles to identify statements claiming or implying that experiential trust criteria were met or violated by museum leaders or staff. In addition to the five experiential criteria (competence, reliability, sincerity, integrity, and benevolence), we coded comments related to a sense of belonging in a team or broader museum community.

About This Article

We gratefully acknowledge project support and funding from Innovation Resource Center for Human Resources (IRC4HR®).

Want to learn more about trust? The best place to start is our “Trust 101” primer. From there, take a look at our trustworthiness model, our work on why benevolence is key to our perceptions of trustworthiness, our research into how people assess the trustworthiness of zoos and aquariums, a conversation about the role of trust in public health, some findings pertaining to the role of partnerships in trust-building, and our thoughts about how moral motives factor into considerations of trust and trustworthiness.

Photo courtesy of Cherrydeck @ Unsplash.