Employee Assessments of Leader Trustworthiness

How employees assess leader trustworthiness under a variety of workplace conditions.

As part of our ongoing Culture of Trust project, we and our partners at the Association of Science and Technology Centers (ASTC) and the Association of Children's Museums (ACM) are developing strategies for building, maintaining, and repairing trust between leaders and staff in the workplace. In previous blog posts, we identified the components of trust that come into play during leader-staff disputes and summarized key trust-building strategies detailed in the literature. We also explored leader responses to contentious workplace issues. In this post, we share findings from the project's fourth and final component: a study of staff experiences of (and perspectives on) workplace trust.

To learn about these experiences, we administered a survey to non-managerial staff employed in the non-profit arts, culture, and leisure sectors. Our results provide in-depth insights into employee assessments of leader trustworthiness-both in the presence and absence of organizational conflict and under conditions of leader action and inaction.

Employee Evaluations of Trust

After seeing how closely leaders' actions aligned with our trust framework, we created a survey designed to reveal how much staff trust their leaders relative to the experience-based trust criteria of competence, reliability, sincerity, integrity, and benevolence. Our specific goals were to answer the following questions:

- To what extent is staff trust in leadership affected by the combination of two situational factors: (a) the presence or absence of contention in the workplace, and (b) whether leaders took actions in response to contention?

- To what extent do the five experience-based criteria of trust (competence, reliability, sincerity, integrity, and benevolence) vary based on the combination of these situational factors?

Initially, we sought responses from non-managerial staff in the museum field. Due to low response rates, we expanded our survey to include employees working within the arts, culture, and leisure sectors. Ultimately, very few museum staff responded to the survey — and some respondents were employed in for-profit organizations. Despite this, responses did not differ on the basis of organization type or sector. The fact that our sample reaches into all manner of cultural institutions makes the findings more generalizable.

How much trust do employees place in their leaders? To answer this question, we first asked employees if they had experienced workplace conflicts related to a variety of topics (including financial matters, working conditions, leadership styles, generational differences, and organizational stances on social or political issues). We then asked if their leaders had taken any number of actions in response to these conflicts — for example, improving information sharing, enhancing opportunities for staff to provide input, increasing staff compensation and support, etc. In the final section of the survey, we gauged employees' feelings about their leaders by asking them to rate how strongly select words (for example, "conscientious," "dutiful," and "candid") described their employers. Participants were neither explicitly asked whether they trusted their employers nor explicitly told that the select words they responded to were related to criteria of trust.

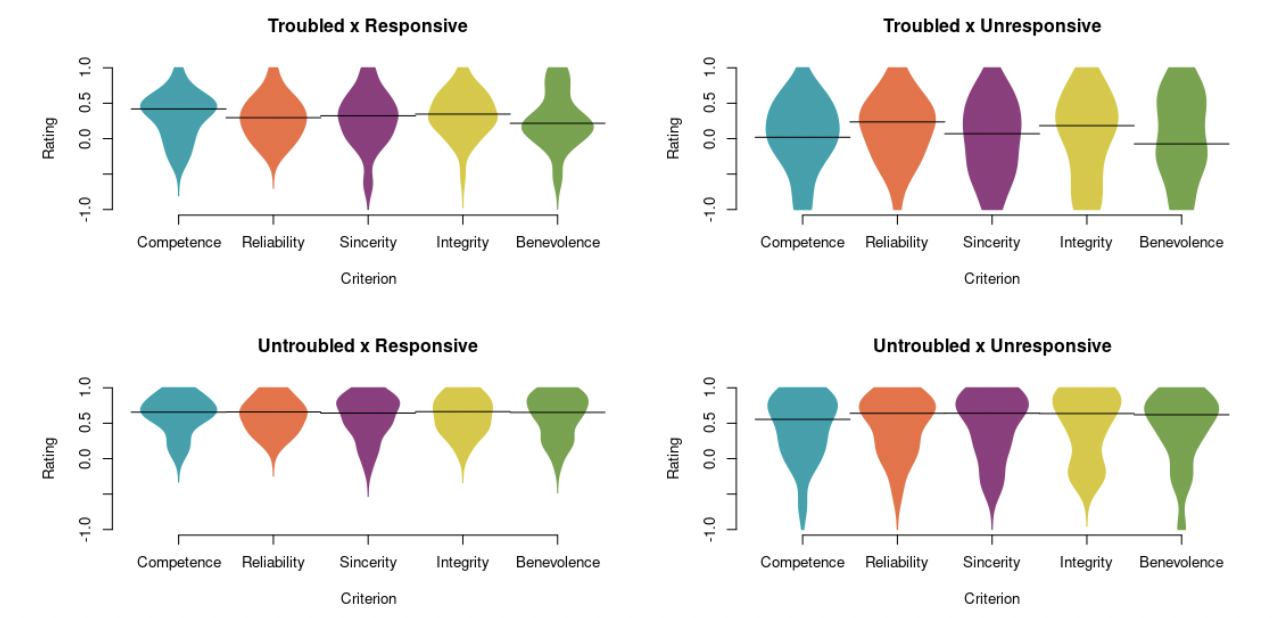

The figure below presents the results of our survey as a set of violin plots, the "bodies'' of which offer several features for visual analysis. The length shows the estimated range of the data, and the shape shows where to find the bulk of the observations (emphasized with the horizontal line marking the median). For reference, imagine the violin plot for the normal distribution: it would look a bit like a lemon, with a pronounced belly at the center and short, symmetric protrusions at the top and bottom. The four quadrants of the figure depict levels of trust for each experience-based criterion, under four conditions:

- Troubled x Responsive (top left) — that is, when workplaces are experiencing significant contention and leaders are responding.

- Troubled x Unresponsive (top right) — that is, when workplaces are experiencing significant contention and leaders are not responding.

- Untroubled x Responsive (bottom left) — that is, when workplaces are not experiencing significant contention and leaders are responding.

- Untroubled x Unresponsive (bottom right) — that is, when workplaces are not experiencing significant contention and leaders are not responding.

In each quadrant, ratings for each experiential trust criterion are depicted along the Y axis from a range of -1 to +1. Median ratings for each criterion (i.e., the "body" of each violin) are shown as horizontal black lines.

The bottom right quadrant of the figure (Untroubled x Unresponsive) depicts what trust looks like under "neutral" conditions. Here, one sees the full range of ratings (from -1 to +1) for each criterion. The balloon is narrower on the negative side and fuller on the positive side. This indicates that on the whole, when workplaces are not experiencing many contentious issues, levels of trust for each criterion are relatively high (an average of 0.5).

This changes when troubles arise. As can be seen in the top right quadrant (Troubled x Unresponsive), when leaders are unresponsive to workplace contention, trust ratings drop. The center of gravity for each trust component is lower than in any of the other three conditions, being close to 0 (and below 0 for benevolence). And for each trust component, a significant number of respondents gave negative ratings (far more than in any of the other three conditions). As all of this suggests, when contention is widespread and leaders do little to respond to it, the result is low-trust environments.

On the other hand, our survey results suggest that when leaders take any kind of action (either reactive or proactive) to mitigate contention in the workplace, trust increases. Proactive behaviors seem to be particularly beneficial, as the bottom left quadrant (Untroubled x Responsive) indicates. This condition generated the highest overall trust ratings, with all five trust components above 0.5. This condition also had the fewest number of negative ratings; here, the neutral rating (0) was pretty much the low point of the distribution!

It is perhaps not surprising that troubled workplaces receive lower trust ratings from employees, but as the top left (Troubled x Responsive) quadrant indicates, leader actions do create higher-trust environments than would otherwise be the case. All five trust criteria received positive ratings here, with competence being particularly high (near 0.5).

Let's Put it To Work

All in all, the results of our employee survey indicate that responsive leaders keep the center of gravity in the positive range. Unresponsive leaders widen the distribution of responses and push employees towards, if not into, negative territory. Proactive efforts in the absence of troubles does actually seem to build trust. We can't say whether this helps organizations avoid troubles altogether or if those organizations have banked enough trust to weather any trouble. What we can say is that these organizations are operating in a much higher-trust environment than the untroubled organizations where leaders do nothing special.

With regard to our second research question, our results are more mixed. On the one hand, ratings on each of the criteria were highly correlated within each condition. But there were two (partial) exceptions to this trend. The first pertains to competence. In the "troubled and unresponsive condition," the center of gravity was lower. The more negative ratings here suggests that employees in these organizations are starting to doubt the ability of their leaders to respond to workplace trouble. To counteract this, the best thing leaders can do is to act — the more transparently, the better. Even if their responses are still in the planning stages, by sharing information about what they intend to do to resolve workplace disputes, leaders can build employee trust. Including employees in the planning process is an even better approach, as this demonstrates not just competence, but also sincerity and integrity.

The second exception pertains to benevolence. In both "troubled" scenarios (top left and right), benevolence received the most negative responses. This suggests that employees at troubled organizations do not feel leaders are addressing their needs — even when they do respond to trouble. This echoes more general findings from our trust research. In study after study, we've found that benevolence is often the missing link in organization's trust-building efforts. This may explain why employees generally rated leaders lower on this component of trust, and provides further support for the idea that acts of compassion and care are key to improving perceptions of trustworthiness. And here, leaders may find it helpful to bear in mind that their goal is not only to keep their organizations whole and well-functioning, but also, to ensure that their employees are whole and well-functioning.

About This Article

Culture of Trust is supported by a grant from the Innovation Resource Center for Human Resources. Since launching this project, we've analyzed news media coverage of leader-staff disputes to identify the components of trust that most often come into play when contentious issues arise in museum workplaces and reviewed the existing academic literature on leadership-staff trust in nonprofit organizations to identify key strategies for fostering employee trust.

To learn more about our work on trust and trustworthiness, see our "Trust 101" explainer along with blog posts on partnerships and trust-building, public trust in zoos and aquariums, and our moral motives conference.

Photo courtesy of Vitaly Gariev @ Unsplash