Numbers in the News: Caveats & Credibility

This edition of the Number in the News series studies the effect of explicit caveats in news stories on audiences. The results reported here are based on a single experiment in a larger sequence of experiments

Can the news help you learn statistics? In this series of studies, we’re asking people to read, watch, or listen to one of two versions of a news report that contains numbers, visualizations, or both. Then we’re asking them a series of questions about the credibility of that news report and some of the inferences they make from that presentation. These are the two dependent variables common to all our studies. In addition, we are asking people to assess the relevance of the story topic to four ever-widening social scales: “me”, “my close family and friends”, “people who live near me”, and “society as a whole.” For details about Numbers in the News and the hypothetical model that underlies this research, click here.

The A/B Test

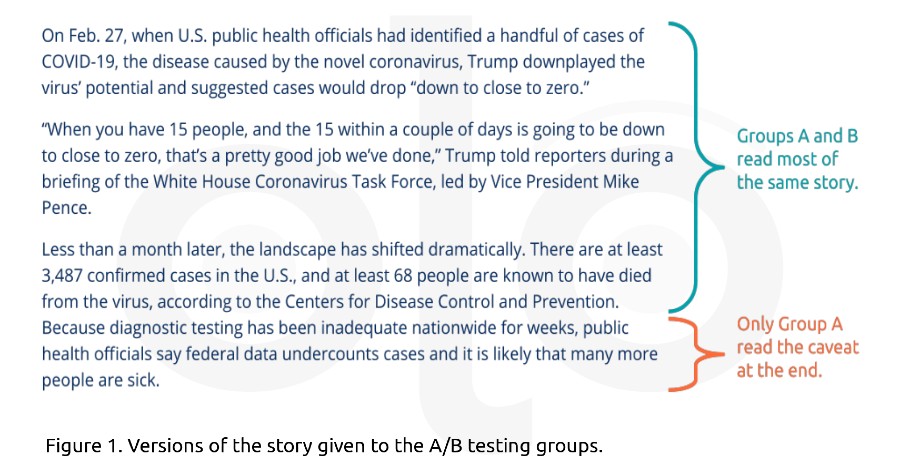

Journalists have been qualifying COVID-19 case and death counts as “confirmed” or “known”, often with explicit caveats about the quality of the data. The published version of the story (Story A) included a sentence that communicated some uncertainty about the actual number of cases; the alternate version (Story B) did not.

Key Findings

Social Relevance

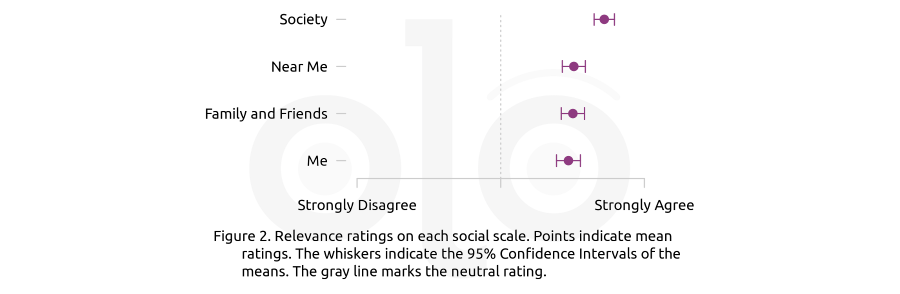

We asked respondents to rate the relevance of the story at four ever-widening scales: “me”, “my close family and friends”, “people who live near me”, and “society as a whole.” Figure 2 shows the average (mean) relevance rating for each social scale. Participants in both groups rated the story’s relevance similarly to one another at all social scales. Both groups found the story more relevant to “society as a whole” than at other social scales. That means that judgments about social relevance depended on the respondents, and not the story version to which they were assigned.

Credibility

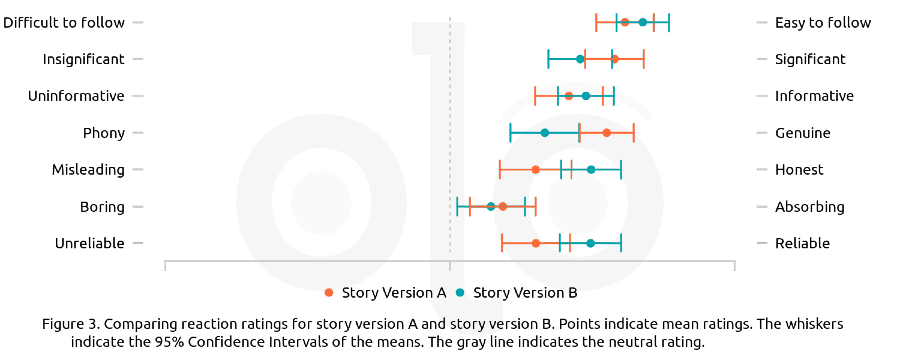

We asked respondents to rate their reactions to the news stories they read. These reactions capture particular aspects of the credibility that respondents ascribe to the stories. Figure 3 shows the average (mean) ratings for each reaction. It shows that there are some differences in audiences’ reactions that depend on the version of the story they read. We corroborated the differences between story versions using multiple statistical tests. All else being equal (in terms of political affinities, judgments of social relevance, demographics, and other variables), we found that people who read the version without the caveat gave more positive ratings (more reliable, absorbing, honest, and so on). In fact, judgments of social relevance mattered more.

Inferences

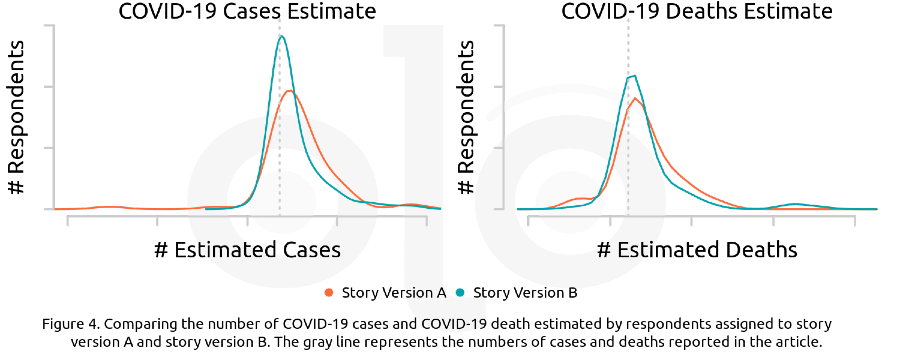

Since the caveat explicitly noted that official numbers are likely to be undercounts, we asked survey participants to estimate the true number of cases and deaths from COVID-19 based on the information they saw. We thought people who saw the caveat would make higher estimates. Survey participants’ estimates of COVID-19 case and death counts were similar across versions, as the side-by-side graphs in Figure 4 indicate (the dotted line represents the official numbers reported in the story). All else being equal, we found that people who saw the caveat estimated that there were more COVID-19 cases and deaths even though overall, people’s estimates were close to those provided in the story.

Perceived Topic

When we asked respondents to explain their social relevance ratings, many respondents - regardless of political affiliation—focused on a perceived criticism of the government, rather than the topic of COVID-19 as a whole. Both versions of the story explicitly fact-check a politician’s statements about the virus, which may explain why people had the responses that they did. And this perception that the story was critical may have overridden the potential effect of the caveat for audiences. We can test this explicitly in future experiments.

Recommendations

- When reporting numbers in the news, be honest about what you know and what you don’t know. While it may make audiences more critical in the short-term, helping people reason about ambiguity is the purpose of teaching statistical literacy.

- When reporting numbers in the news, mentioning politicians by name may polarize audiences and draw attention away from the rest of the story. Be especially careful about evaluative language in these contexts, as it could alienate audiences.

Funding

These materials were produced for Meaningful Math, a research project funded through National Science Foundation Award #DRL-1906802. The authors are solely responsible for the content on this page.

Photo by clay banks on Unsplash